The Ness Yole and The Orkney Yawl – Two types of northern boat

Yachting World of July 17 [1936] contains an article by Arthur Johnston on types of boats in use in the Northern islands, and the succeeding issue a photograph of models of the Shetland and Orkney types of boats which are shown at the Exhibition of British Fishing Boats at the Science Museum, South Kensington. Mr Johnston’s article is as follows:-

Both of these boats from the Northern Islands show their Viking origin with minor adjustments in hull-form and rig that are the natural development of use for different purposes.

The Ness yawl is perhaps the nearest to the original type of longboat used by the early colonists who came from the Baltic districts, and although of smaller size is still used for very similar sea work; for the rowing as easily as possible in the sort of wild water that results from hard wind against strong tides.

For Stiffness

The Orkney boat, however, had to be of greater carrying capacity and so shows a stiffer section, greater beam for sailing, with oar work more in the nature of an auxiliary means of progression. Fishings are usually carried on near the coast or in the narrows where the current is strong and the sea in a gale deeper, heavier and more broken. Even in the case of banks at a considerable distance out, the shallowness of the water causes a heavier sea. The fisherman thus occupies a dangerous position.

Rowing Only

The ness, Yole or Jol hails from the most sotherly part of the Shetlands, known as Dunrossness – hence the word Ness (Yole) and is peculiar to this district. It is a long, low narrow boat mostly used for rowing. Saith or Cole fish were commonly caught by this type of boat, which was rowed by two men, who hold an oar in each hand. Besides the two rowers there are two others who sit one forward, the other in the stern, with a line thrown out on the tide side. The two men row or ‘andoo’, as they term it, as steadily as they can while the other two are employed in observing the lines. When the tide is running hard these float near the surface of the water.

As the tide gets weaker the fish go farther down and a sinker, usually made of lead and weighing about 11/2 lb, is used to let down the hooks to about 20 fathoms. They are then hauled up as quickly as possible. By this means the saith are deceived by the motion of the bait, which they possibly think is alive, and are readily taken. This method the fishermen call dragging for fish.

Rigged with a square sail and mast near the centre, these boats might be described as the true ‘Norway Yawls’, having very much the build and character of whale boats. They were handled in a wonderful manner by the Shetlanders, who, in their love for the sea and by their daring and energy on it, show themselves still worthy of that descent from the Norsemen of which they are all so proud.

Fast Tides

Round Sumburgh Head and the many points and promontories between the rocks and islands, the dangerous tideway known as the roost runs at a terrific rate, and in these boats they will ‘cut the string’, which means crossing these tideways. Usually this is only attempted at slack tides, but when necessity arises, and it has to be done at full tides, the danger is extreme.

Sometimes the livers of the fish were crushed to make oil and prevent the sea breaking and oft times they had to ‘up and off’ owing to the suddenness of a storm and either row for hours to make the land or scud before it under bare poles.

Quite Inferior

About 150 years ago, more or less, the boat in use throughout the Orkneys was much inferior in model, construction and rig to those of the present day. The smaller boats then in use were low, flattish things with straight stem and sternpost raking considerably, fastened with tree nails, sometimes carrying one sail, sometimes two, and very often more oars doing the work.

Orcadians are not all perhaps such thoroughbred fishermen as the Shetlanders and were somewhat reluctant to follow up this profession under many hazards, for farming is their chief industry.

General Transport

The Orkney boats were often employed for general purposes, such as carrying fuel across the sounds, conveying corn to the mill. Shipping kelp or carrying provisions, etc., to and from the nearest town. In the older boats the fishing was not followed with zest owing to the rapid tides among the islands and the frequent bad weather, serious handicaps to men who are not well found in boats and gear. The later Orkney boat carries a jib and two large lugs. Usually the after lug is rigged with a boom.

Of the same type as the old ‘straight stems’, they are remarkably improved. The stem has now a fine curve, the hold is deeper and the mould fuller. They are now copper fastened throughout, painted or varnished instead of being tarred.

They also used to be rigged with sprit sails. Apparently they found this rig most handy and safe, and were often in use on boats from 11 to 15ft. Keel, which were constantly being used for either fishing (line), lobster fishing, or general use. The sail was laced to the mast, and both were unshipped and carried on shore or stepped together.

Piloting was another venture of the Orcadians, but it is today practised with motor boats. Previous to this, a larger boat of the class 15 to 18ft. keel used to go considerable distances from the land in the hope of picking up a vessel and navigating her past the dangerous islands. They used to have a herring fishing boat measuring from 30 to 36ft. in keel, but they have long since been discarded and hardly any boats from Orkney pursue the herring fishing today.

With a population scattered over a number of islands, boats are a necessary means of communication between them, hence the boat in these parts will always remain in use. Orkney tides – in many places the stream runs at the rate of 6 to 7 knots. At one time, and, in fact, still, it may be said of the people of Orkney that they can scarce step over their threshold without their boats.

[Transcribed from an article in the Orcadian, October 15, 1936 and posted with the consent of the Orcadian]

Permission to reproduce the following article on this website has been granted from the publishers, Seaforth Publishing, for use by Orkney Historic Boat Society only.

The Boats of Orkney and Pentland

From the book ‘Inshore Craft, Traditional Working Vessels of the British Isles’ edited by Basil Greenhill and Julian Mannering

Orkney Yole

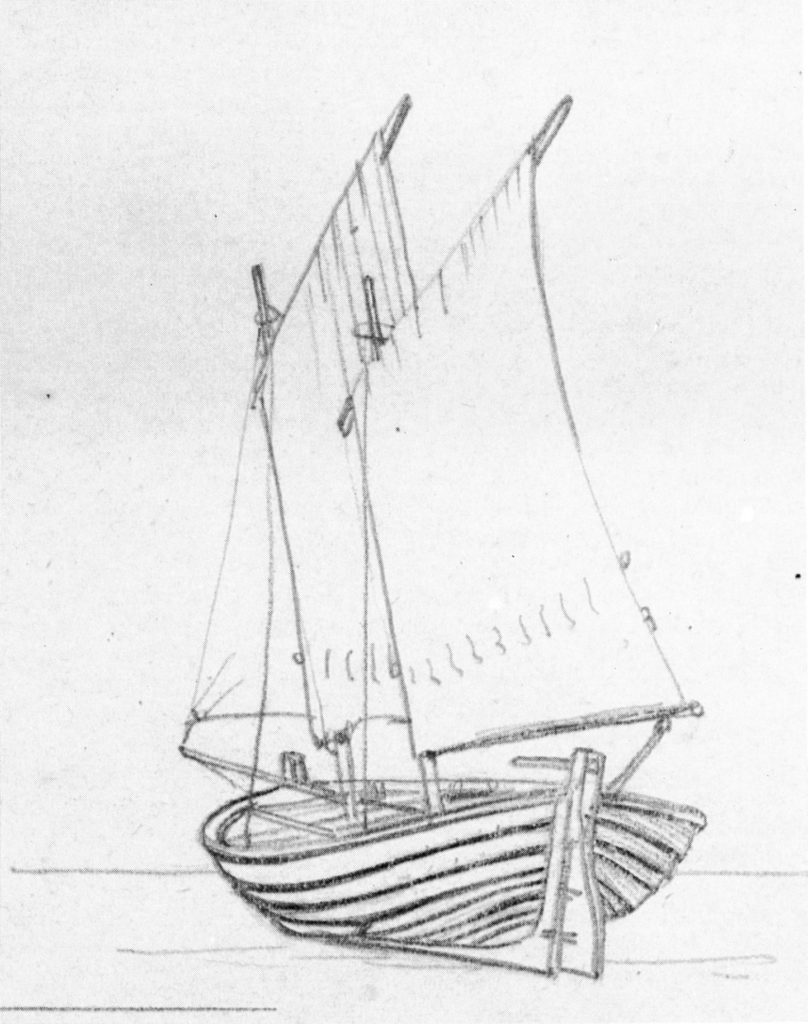

Open, double ended boats that, although generally less than 20ft in length, incorporated sufficient carrying capacity for inter-island transport or subsistence activities, and which, characteristically, were worked under easily handled, two masted rigs.

Typified by their substantial beam and ample internal volume, Orkney yoles were once found throughout the entire island group, whilst the finer lined skiff was restricted to the northern isles only. Both types were of shell clinker construction but, compared to their Shetland counterparts, they had far more strakes and were stiffened by a closer-spaced framing system (with discontinuous elements). Original imports of Norwegian boat timber declined in the nineteenth century and Scottish materials became dominant. Oak was used for keels, stems, aprons and frames, with Norwegian white pine or Scottish larch for planking; spars remained of pine. Copper fastenings and steamed timbers were largely twentieth-century introductions.

Building was largely carried out by several recognised part-time, family based boatbuilders. Builders in the North Isles included Miller of Westray and Omond of Sanday, whilst in the South Isles several generations of the Duncan’s of Burray were prominent, as was Nicolson of Flotta. There were significant contributions from the shipyards and yard-trained workers (such as Baikie) of Stromness and Kirkwall too. Boats of the largest class ran from 12ft to 12ft 9in on the keel with over 7ft beam, whilst the smaller class were around 11ft on the keel. The larger boats sported distinctive two masted rigs, with mainmasts positioned amidships and their, slightly taller, foremasts well forward; smaller boats were single masted. Oars worked between double tholes, were definitely considered an auxiliary to sail, for calms, and helping cross tidal streams.

Documentary, early pictorial, and comparative evidences point to these boats’ origins in pre-nineteenth-century imports of ‘Norroway’ boats. But the significant changes in hull design and building technology which followed suggest some acculturation from mainland practices, although the major thrusts of development seem to have remained Orkney ones. The origins of the distinctive two masted Orkney rigs remains speculative. Already well developed in the mid-nineteenth century, it seems that their appearance may date from the late-eighteenth when, as a longstanding maritime crossroads’, Orkney’s seafarers had been exposed to a wide variety of boat-using experiences, including naval small craft, Dutch busses, Irish wherries, Greenland whaleboats, and service in the Navy and the Hudson’s Bay Company.

Yole usage was centred around crofting, inter-island transport, and subsistence rather than cash crop fishing. The latter did feature from time to time, though only the fisherman of North Ronaldsay, the northernmost isle, had a high reputation. Inevitably, activates such as pilotage, lifesaving and, sometimes lucrative, salvage work featured too. Today, though not of yole design, the modem Orkney creel boat is well regarded, with its users continuing what began as a successful late eighteenth-century fishery.

North Isles Yole

Though apparently similar to the South Isles yole of the early twentieth century, the North Isles yole which survived it was built with more widely spaced frames and had slightly more upright stems and greater beam. This marked beam, some 7ft 6in on 17ft overall length, helped make a dry boat of considerable capacity, capable of carrying 1-2 tons of farm produce (including livestock). But the hull form still provided the shallow draft needed for manual handling at the home ‘boat noust’, or for working loads at open landings. However, a deepish keel surmounted by vertical garboards provided good grip on the water when sailing. The standing lug sails of the two masted rig were loose footed, but the main was extended along a (gooseneck pivoted) boom by a clew traveller. The two lugs, together with a jib on a bowsprit, made for an effective and manageable sail plan. Smaller yoles carried a single dipping lug sail and compared to their South Isles equivalents, had more upright stems and less flare in the ends. No examples of the large yoles are thought to survive, though one or two of the smaller types remain.

Westray Skiff

(North Isles skiff)

Though occurring in the same areas as the North Isles yole, the skiff was of narrower hull form, with slacker bilges and finer ends (especially aft). It provided a more easily driven and Weatherly hull, though it had less carrying capacity and was wetter. Large skiffs, which Characteristically, were worked under easily handled, two masted rigs, measured, up to 19ft 6in overall by 6ft 4in beam, carried a standing lug sail and a jib set to a bowsprit. The smaller skiffs, around 14ft 9in by 5ft 10in, set a dipping lug only.

Although sometimes linked to the yoals of Shetland (qv), the straight stemmed Westray skiff does not really evidence their extremes of hull form and appears unrelated. However, its potential performance did see it survive into the modern regatta era, albeit with part decking and a stayed, Bermudan sloop, dinghy rig.

South Isles Yole

As the working counterparts of the yoles of the North Isles, these South Isles yoles appeared similar in many respects but exhibited a few significant differences. Typically, of ten strake a side construction, their frame spacing was rather narrow, with continuous (gunwale-to-gunwale) frames and floors alternated with paired (‘floating”) frames, these latter running from

the gunwale to the garboard stroke top only. Typically, a large yole was around 18ft length overall, by 7ft 2in beam, at a keel length of some 12ft to 12ft 8in.

Famously, they set a two sailed spritsail rig, using unstayed, keel stepped masts supported by thwarts. Mast length was around four-fifths of overall boat length, with the foremast slightly higher than the main, and each was positioned one-sixth and one-half of the boat’s length from the fore stemhead respectively. The foresail was loose footed whilst the main was

rigged to a boom (especially when racing or sometimes a short club was set outboard to improve sheeting). The spritsails were cut with some peak, a rope cringle in the head receiving the tip of the sprit whilst the heel was slung in a ‘Shangie’ (a rope grommet, bighted round the mast, which provided a simply-adjusted support). The smaller yoles, of around 11ft on the keel

(15ft overall, by 6ft 4in beam), used a single mast positioned about one-quarter of the boat’s length inboard, setting a single, loose footed, boomless spritsail with accompanying jib and bowsprit.

Though motors were fitted from early in the century, by the 1950s the large yoles survived as pleasure and racing craft only, usually re-sparred with a stayed mast and bowsprit, setting a Gunter main and jib.

Stroma yole

Though bearing Orkney yole characteristics, this distinctive double ender was used exclusively from the Caithness island of Stroma off the southern shore of the Pentland Firth. To cope with the extreme tidal streams and seas which their users might encounter, these large yoles were more barrel chested above the waterline than their Orkney counterparts and carried two extra topside strakes for greater freeboard. Underwater, they exhibited the characteristic standing strakes and relatively fine ends flared above. Strongly constructed by shell clinker methods, their internal framing (which was not commenced until half a dozen strakes were raised) alternated continuous and discontinuous elements, with floors bolted to the keel. Later boats at least had larch planking, and larger motorised ones might bear decking.

They were built to 12ft, 14ft and even 18ft on the keel and were typically, and respectively, used for inshore lobstering, working the tidal streams when hand lining for cod and crossing with cattle to the mainland, and bringing fuel and goods home. Sailing rig was Orkney style, with two spritsails and a jib for boats under 15 ft of keel, and two lug sails and a jib for larger ones. Island families might possess one or two boats of different sizes, kept in ‘geos’ (narrow inlets) or hauled ashore.

Stroma-based boatbuilding is believed to have stemmed from one Donald Smith, who learnt yole building from John Duncan of South Ronaldsay (Orkney) early in the nineteenth century. Smith is said to have incorporated features from a Norwegian boat washed ashore on Stroma in his eventual design, and his apprentices, Simpson and Banks, continued his work. The former commenced building on Stroma in 1845 and, amazingly’, built the last boat there in 1913. Stroma’s later carpenter boatbuilders also included Donald Smith senior and junior, and Donald Banks. Though the island was largely de-populated by the late 1950s, the reputation of Stroma’s yoles was such that many survived in nearby mainland use until modem times, and copies have also been built.

Sources

Much previously published material on Orkney boats is rather superficial and repetitive, so that this contributor has been privileged indeed to have been allowed to draw upon the insight and unpublished research material generously provided by the Orkney-born naval architect, Dennis Davidson.

Elsewhere, Michael Marshall, ‘Fishing, the Coastal Tradition’ (London 1987), contains some evocative and informative material on Stroma and its yoles, whilst ‘Working Boats of Britain’ illustrates their hull form and typology with great clarity. Much incidental information and source work is contained in Alexander Fenton, ‘The Northern Isles: Orkney and Shetland’ (Edinburgh 1987) whilst ‘Deep Sea Fishing and Fishing Boats’ has a classic illustration and description of the Orkney yole.